The following article was published in the bi-annual journal 'Studies in Sikhism & Comparative Religion', Vol.XXIX, No.1, January-June 2010, Guru Nanak Foundation, New Delhi

How, why and when the concept of creation and preservation of all the animate and inanimate beings on planet earth and the entire gamut of universe around it got attributed to an Invisible yet All Pervasive Power - call it God or by one of other countless names in myriad of languages - originated has remained as mysterious a secret as ever for all the most diligent, dedicated and the cleverest inquisitive seekers. The 'Godhood' has been the most ennobling uniting as well as single deadliest divisive force in the history of humanity. It could be concluded with all the evidence available in the most authentic chronological details that all the big battles fought by the mightiest and - even those considered wisest and noblest - of various rulers were, after all, for meager earthly gains and soundly selfish reasons, though often invoking unearthly and 'higher heavenly' considerations in the names of new and ancient faiths. It is, therefore, with a much greater degree of solace that one can turn to the mystical Islam, popularly known as Sufism, for its emphatically stated principles of promoting a deeper sense of fellow feeling among practitioners of the different faiths envisioned in different segments of the only a planet proven inhabited by the species that has dared to conjure up the most fascinating 'dream-like-reality' of Godhood .

Interestingly, it was not till as late as early nineteenth century that the Western scholars of Islam popularised the term 'Sufism' for Islamic mysticism - then called Tasawwuf, literally to dress in wool, in Arabic, and Sufi being itself an abstract word from Suf - wool - obviously a reference to the coarse woolen garments worn by early Islamic ascetics. The words fuqura, plural of Arabic Faqir and Persian darvish - both meaning the 'poor' also used for the Sufis soon got elevated to be words of English. Though the sources Islamic mysticism have been variously traced to non-Islamic traditions - the Prophet is quoted, "There is no monkery in Islam", it is now widely accepted that the elements of the ideology emerged as a reaction and counter measure to 'increasing worldliness' and luxurious living of the fast expanding Muslim community of Arabs as rulers in the near and far flung new territories with many of them of them having highly developed religion-cultural traditions. The Sufis sought to solace and calm down the people by exhorting them to deepen their spiritual well being - and they were viewed better than the stern sharia enforcers. The Sufis were soon in the forefront of the missionary activity in the rapidly growing Islamic world. It goes to the credit of Sufis that they imparted a wider and more acceptable imagery to the Prophet and enlarged the scope of Muslim Piety. The creative Sufis gifted with literary accomplishments skillfully employed the local languages, often bursting out in sublime poetry, in the service of spreading Islam in Iran, Turkey, India and lands far, far beyond.

The evolution of Islamic mysticism included the stages of early asceticism and constant meditation in the pious circles as reaction against materialism that had set in during Umayad period (661-749). This was followed by increase in the fraternal groups of Sufis. It was Rabiah al-Adawiyah, a young lady of Basra, who is credited with developing the Sufi ideal of a love of God - seeking no reward of Paradise, having no fear of hell. The Iraqi school of mysticism founded by al-Muhasibi (d-857), further advanced by Junayad of Baghdad (d-910), laid emphasis on strict self control and 'purging of the soul' and tawakkul - absolute trust in God. The Egyptian Sufi Dhu an-Nun (d-859) introduce ma rifah - interior knowledge - in contrast to 'learnedness', while Iranian Abu Yazid al-Bistami (d-874) contributed the significant concept about annihilation of self, Fana - the sparkling symbolism that ignited the imagination of generations of later day brilliant mystical poets. The theosophical theorists of mystical dimensions of man's sojourn in this world and the Immensity of the personality of Prophet could not be far behind. This trail blazed by Sahl at-Tustari (d-c.896) was diverted to dazzling heights by his disciple al-Husayn ibn Mansur al-Hallaj whose proclamation, Ana al-Haqq "I am the (creative) Truth" - derived from the thesis that God created Adam, "in His own image" - so infuriated the theologians of Shariat that they got him executed in 922 in Baghdad. Mansur, in his death, was soon to be consecrated as the, 'martyr of love' and his poems and other writings are considered the most exquisite examples of mysticism around the personality of the Prophet. Adopting an attitude of not needlessly provoking the orthodox theologists, the Sufis operated in smaller circles during the earlier centuries of Islam. They preferred to underline their adherence to established theological traditions. Abu Hamid al-Ghazali (d-1111), in his numerous writings including Ihya Ulum ad-din - the Revival of Religious Sciences - advocated moderation in the tendency in mysticism of equating God and the world.

The 13th century witnessed a further crystallization of the Sufi thoughts. The Spanish born Ibn al Arabi, elaborating on the relation of God and world and the underlying divine reality, put forward the theory of, "Unity of Being". The Egyptian Ibn al-Farid, the Persian Farid od-Din Attar (d-c.1220) wrote the finest mystical poetry while Central Asian Najmuddin Kubra discussed at length the psychological experiences of the mystics. It was, however, the poetic-philosophical genius of Jalal ad-Din Rumi (1207-'73) whose Masnavi in about 26000 couplets, dedicated to his mystical-master-beloved Shams ad-Din of Tabriz, is a rare compendium of broader religious ideas. Rumi became inspiration for whirling dervishes who promoted elaborate dance rituals and music for 'purificatory ecstasy' of the soul. Rumi's mystical poetic strains found resounding echoes in works of his younger contemporary Turkish Yunus Emre and Egyptian ash-Shadhili (d-1258). This was the period when Sufis became torch bearers of message Islam across the continents. The encounters with the Hindu traditions of mysticism encompassing the idea of divine unity and the Buddhist practices in Central Asia of life in Viharas in closer proximity to people for their service and welfare not to speak of the adversarial proximity with some grudging admiration for activities of social service by the Christian and even Jewish seminaries. The Sufis were inclined to pick up relevant elements from here and there in the cultures of alien lands as long they could serve the purpose of spreading the message of Prophet in conformity with the evolving Islamic Sunna. They were guided by the divine wisdom contained in the Quran, 'to be interpreted with increasing insight'. The doctrine of the Last Judgement; the assertion that, 'God loves them (mankind) and they love Him'; the strictly regulated life of Prophet - all provide the strong spiritual anchor of Sufism. Another fundamental concern in Islam has been Tawhid, "There is no deity but God" which thinker Junayd Baghdadi (d-910) had tried to explain, "Recognising God as He was before creation". The two aspects - God and creation - as one Immanent reality, Wahdat al-Wujud, were further reinforced in terms of Tawhid to mean that there is nothing existent but God.

Though Sufism had certainly been developing a distinct character by the twelfth century, great Sufi saints in the length and breadth of the vast Islamic empire were not rigidly disposed to fine tuning the nuances of the faith when under compulsions of commandments of the kings and what would work with the people. The Sufi influence in India came from north west when Shaikh Ali Hujwairi (d-c1079), widely known for his work Kashf al-Mahjub, settled in Lahore - his Shrine has been attracting a constant stream of devotees professing all faiths. Shaikh Muinuddin Chishti (1142-1236) estabilished himself in Ajmer after Shihabuddin Ghori defeated Prithvi Raj. Shaikh Bahauddin Zakaria(1176-1271), after blessing by Shihab al-Din Suhravardi of Baghdad, came down to Multan. The Sufi orders, silsilas, mentioned to be 14 in the Ain-e-Akbari had a vast expansion with the consolidation of Muslim rule in India - the most important being the Chishtia, Suhrawardia, Naqashbandia, Qadria, Firdausia, Shattria among the 'orthodox' and the Qalandars and Madars among the 'unorthodox'. With passage of time, many Sufi saints like Shaikh Muinuddin Chishti, Hazrat Ali bin Uthman - popular as Data Ganj Baksh - Shaikh Bahaauddin Zkaria, Shaikh Fariduddin Ganj-e-Shakar (1175-1265), Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya, Hazrat Mian Muhammad Mir (1585-1655) have become the most adored ones with their tombs becoming places of pilgrimage and huge popular fairs. While most of the Sufi saints shunned the seats of power and kept a safe distance from the rulers even when sought after, some others were known to play politics and influence peddling. There were trying situations during struggles of royal successions which got murkier and bloodier in history and Sufi leaders had to pay for their proximity to the losers. Dara Shakoh, the crown Prince designate by Shahjahan was not destined to be 'the Sufi King of Hindustan': and his spiritual guide and friend Sarmad, the naked Sufi poet, became Mansur of India and Prince among martyrs of faith.

The Sufism has indeed left a strong imprint not only on the socio-religious history of India but has also made lasting contribution in the realms of literature, arts, philosophy, music, crafts and other dimensions of national life. The Sufis were, in their own way, the harbingers of 'soft power' of globalisation and even the dialogue of civilizations in their times. The concept of composite culture of the sub-continent can be traced to doors of the khanqahs of the Sufis. The Sufi centres encouraged and provided for education and learning among the masses.The message of social equality, particularly against the curse of the Caste system in Hinduism was never conveyed so loud and clear in theory and practice as by the Sufi derveshes. They were often advocating the causes of the poor and the deprived sections of society. Being tireless travellers, the Sufis propagated bridging of narrow cultural divides. The twin towers of strength of Sufis were their aquida ie faith and ishq that is love - both for Allah and his makhluq - creation. To quote Hazrat Bayazid Bistami:

As for India, the partition of the country on the basis of an untenable communal ideology has involved the challenging task of renewal of values of communal harmony not only in in India but tellingly in predominantly Muslim Pakistan too - what the Sufis had tenaciously worked to accomplish. No wonder that the studies in Sufism have been increasingly encouraged in higher academic institutions and there is tremendous interest in the movement epitomising Majma-al Bahrain - Mingling of Two Oceans - Hindu and Muslim mystical ideas. The most palpable and profound impression of Sufism has been in literature of various Indian languages. The Sufi impulses have inspired the sublimest poetry with the celebrated saints preferring the local regional tongues for the most intimate communion about the universal divinity for all. The poetry of Ameer Khusrow, Baba Farid, Kabir and many more in Bhakti-Sufi tradition, not to speak of later Urdu, Hindi, Sindhi and Panjabi poets but also the idiom of progressives, indeed draw upon the core of the span and spectrum of the rainbow of India's Bhakti-Sufistic heritage.

According to eminent Urdu writer - thinker Ali Jawad Zaidi, the Sufis were indeed the pioneers in promoting Urdu using sayings - malfuzad - and Dohas to serve their missionary purposes. Sheikh Gangoi was a great poet of Braj Bhasha and also wrote in Hindi under the pen-name of Alakhdas. The echo of Sufi sayings and ideas is apparently distinct in hymns of Namdeva (1270-1350) of Marathwada. Kabir (c1399-1515), the weaver, has been rightly hailed as one of the most popular saint poets of India who wove magic in a simpler language to convey his forthright views on the prevailing socio-religious hypocrisy. The celebrated Hindi critic Acharya Hazari Prasad Diwedi has commented that, "Kabir had a rare and powerful grip on language...he had no peer in the use of to satire and irony...he hit (hypocrites) so hard in simple and chaste words that the target had no choice but flee in surprise...he indeed holds a unique position in the millennium of Hindi literature". Kabir says it all in his inimitable way:

Among other saint poets in the fraternity of sufis, mention must be made

of Sant Dadu Dayal, Mallookdas, Dharam Das and the Prem Marg - love path - saints like Kutuban of Jaunpur, Mamjhan who wrote Madhumalati, Malik Mohammad Jaysi of Padmavat fame, Usman of Ghazipur etc. The land of Sindh, the seat of the earliest civilization on the banks of the legendary river which has imparted its name to the country, had its own intimate interaction with Sufism with the mystical domain of Sindhi poetry led by Qazi Qadan (1463-1551) followed by Shah Abdul Karim (1536-1623) known for his beautiful Baits, Shah Inat (c1623-1712), Shah Latif (1689-1752) famous for long wail of firaq - separation - in Risalo and Sachal Sarmast (1739-1812) who composed beautiful kaafis and Ghazals. Sindhi sufi poets were also great integrators and remained above any narrow sectarian and religious divisions - Shah Abdul Latif says: Bestowal is regardless of caste and creed, all who seek may obtain Him!

It was however,among people of the land of five rivers, always fertile for fresh and healthier all embracing ideas since ages, that Sufism was received with enthusiasm and deeper commitment. Shaikh Baba Farid should be considered among the major figures of renaissance in India whose spiritual insights remain valid even after eight centuries. The inclusion of Farid's evocative hymns and shlokas in the Granth Sahib compiled by Guru Arjan Dev has been a subtle point of reference in the realm of theology in India apart from their literary merit. In the words of Prof Attar Singh, "By admitting these verses into the Guru Granth Sahib, Guru Arjan Dev no doubt added a new dimension and lent them universality by juxtaposing them with religious writing drawn from other traditions." It is interesting to study the medieval Bhakti, Sufi and Sikh poetry to discover that they were all 'struggling against the deadening enslavement to orthodoxies of religions'. Prominent Punjabi Sufi poets including Sultan Bahu (1629-1691), Bulle Shah (1681-1757) and Ali Haidar (1690-1785), following the path shown by Farid, had reacted sharply against indignities based on religion at the behest apparently of Naqashbandis. Even though the process dialogue initiated by the Sufis had a set back in the background of historical circumstances of bloody wars of succession between the Mughal Princes, the frame work of reference for reconciliation had got registered for ever in the minds of a vast majority of people.

What is the contemporary relevance of ideas propounded by the Sufis of sub-continent? Annie Zaidi, a young journalist, has narrated in a charming essay titled, A Little Bit Wild in the Faith Department in her recently released book how generation of young people like her in India - in South Asia as a whole - are irresistibly drawn towards Sufistic ideas and symbols, particularly the music and poetry popularised by Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan's clan and Rabbi Shergill's evocative, Bulla Ki jaana main kaun? not to mention legions of popular singers of of folk tradition and Bhajan circuit led by Hans Raj Hans. The films have also immortalised gems of Sufi poetry. The Deras of different persuasions are comfortable accommodating the Sufi values and some of them like the Radha Soami Satsang Beas have published scholarly commentaries and translations on the works of Sufis like Sarmad, Shaikh Farid, Bulleh Shah etc. The famous Sufi shrines are receiving devotees - expectant visitors - in hundreds of thousands. The state machinery would also appear to be well disposed towards the Sufi heritage in the region. The historians in India have no credible theory to explain mass conversion of people to Islam in India. Harbans Mukhia refers to an essay of 1952 by Prof Muhammad Habib stating that caste oppression might have been a crucial factor among the lower strata of the society. Interestingly, the largest conversions have taken place between mid 19th century and 1941 when Sufism had been in decline due to internal weaknesses. Some Islamists of the Fundamental kind, particularly the Deobandis, likened to Saudi Wahhabis, have been critical of several Sufi practices including the adoration of tombs. It is sadly true that all the faiths proclaim to unite people but every faith has its share of sharply divisive - many times violent - controversies.

In Sufi poetry, the sojourn of a person in the world has been symbolised as musafir - a wayfarer - and a saudagar - a trader - while the world itself is called a Sarai - inn - in the way where traveller / trader has a short stay. Bulleh Shah wishes to travel far, too far to find the Invisible Beloved:

The 21st century had promised to be different for humanity but a decade later the world finds itsef deeply enmeshed in the ancient conflicts of the religious kind - fancifully termed 'clash of civilizations' - with weapons of total annihilation still proliferating while the life sustaining precious natural resources and ecology are fastly dwindling threatening life again in toto! One intuitively turns to pray with words of the Sikh scripture Guru Granth Sahib,

How, why and when the concept of creation and preservation of all the animate and inanimate beings on planet earth and the entire gamut of universe around it got attributed to an Invisible yet All Pervasive Power - call it God or by one of other countless names in myriad of languages - originated has remained as mysterious a secret as ever for all the most diligent, dedicated and the cleverest inquisitive seekers. The 'Godhood' has been the most ennobling uniting as well as single deadliest divisive force in the history of humanity. It could be concluded with all the evidence available in the most authentic chronological details that all the big battles fought by the mightiest and - even those considered wisest and noblest - of various rulers were, after all, for meager earthly gains and soundly selfish reasons, though often invoking unearthly and 'higher heavenly' considerations in the names of new and ancient faiths. It is, therefore, with a much greater degree of solace that one can turn to the mystical Islam, popularly known as Sufism, for its emphatically stated principles of promoting a deeper sense of fellow feeling among practitioners of the different faiths envisioned in different segments of the only a planet proven inhabited by the species that has dared to conjure up the most fascinating 'dream-like-reality' of Godhood .

Interestingly, it was not till as late as early nineteenth century that the Western scholars of Islam popularised the term 'Sufism' for Islamic mysticism - then called Tasawwuf, literally to dress in wool, in Arabic, and Sufi being itself an abstract word from Suf - wool - obviously a reference to the coarse woolen garments worn by early Islamic ascetics. The words fuqura, plural of Arabic Faqir and Persian darvish - both meaning the 'poor' also used for the Sufis soon got elevated to be words of English. Though the sources Islamic mysticism have been variously traced to non-Islamic traditions - the Prophet is quoted, "There is no monkery in Islam", it is now widely accepted that the elements of the ideology emerged as a reaction and counter measure to 'increasing worldliness' and luxurious living of the fast expanding Muslim community of Arabs as rulers in the near and far flung new territories with many of them of them having highly developed religion-cultural traditions. The Sufis sought to solace and calm down the people by exhorting them to deepen their spiritual well being - and they were viewed better than the stern sharia enforcers. The Sufis were soon in the forefront of the missionary activity in the rapidly growing Islamic world. It goes to the credit of Sufis that they imparted a wider and more acceptable imagery to the Prophet and enlarged the scope of Muslim Piety. The creative Sufis gifted with literary accomplishments skillfully employed the local languages, often bursting out in sublime poetry, in the service of spreading Islam in Iran, Turkey, India and lands far, far beyond.

The evolution of Islamic mysticism included the stages of early asceticism and constant meditation in the pious circles as reaction against materialism that had set in during Umayad period (661-749). This was followed by increase in the fraternal groups of Sufis. It was Rabiah al-Adawiyah, a young lady of Basra, who is credited with developing the Sufi ideal of a love of God - seeking no reward of Paradise, having no fear of hell. The Iraqi school of mysticism founded by al-Muhasibi (d-857), further advanced by Junayad of Baghdad (d-910), laid emphasis on strict self control and 'purging of the soul' and tawakkul - absolute trust in God. The Egyptian Sufi Dhu an-Nun (d-859) introduce ma rifah - interior knowledge - in contrast to 'learnedness', while Iranian Abu Yazid al-Bistami (d-874) contributed the significant concept about annihilation of self, Fana - the sparkling symbolism that ignited the imagination of generations of later day brilliant mystical poets. The theosophical theorists of mystical dimensions of man's sojourn in this world and the Immensity of the personality of Prophet could not be far behind. This trail blazed by Sahl at-Tustari (d-c.896) was diverted to dazzling heights by his disciple al-Husayn ibn Mansur al-Hallaj whose proclamation, Ana al-Haqq "I am the (creative) Truth" - derived from the thesis that God created Adam, "in His own image" - so infuriated the theologians of Shariat that they got him executed in 922 in Baghdad. Mansur, in his death, was soon to be consecrated as the, 'martyr of love' and his poems and other writings are considered the most exquisite examples of mysticism around the personality of the Prophet. Adopting an attitude of not needlessly provoking the orthodox theologists, the Sufis operated in smaller circles during the earlier centuries of Islam. They preferred to underline their adherence to established theological traditions. Abu Hamid al-Ghazali (d-1111), in his numerous writings including Ihya Ulum ad-din - the Revival of Religious Sciences - advocated moderation in the tendency in mysticism of equating God and the world.

The 13th century witnessed a further crystallization of the Sufi thoughts. The Spanish born Ibn al Arabi, elaborating on the relation of God and world and the underlying divine reality, put forward the theory of, "Unity of Being". The Egyptian Ibn al-Farid, the Persian Farid od-Din Attar (d-c.1220) wrote the finest mystical poetry while Central Asian Najmuddin Kubra discussed at length the psychological experiences of the mystics. It was, however, the poetic-philosophical genius of Jalal ad-Din Rumi (1207-'73) whose Masnavi in about 26000 couplets, dedicated to his mystical-master-beloved Shams ad-Din of Tabriz, is a rare compendium of broader religious ideas. Rumi became inspiration for whirling dervishes who promoted elaborate dance rituals and music for 'purificatory ecstasy' of the soul. Rumi's mystical poetic strains found resounding echoes in works of his younger contemporary Turkish Yunus Emre and Egyptian ash-Shadhili (d-1258). This was the period when Sufis became torch bearers of message Islam across the continents. The encounters with the Hindu traditions of mysticism encompassing the idea of divine unity and the Buddhist practices in Central Asia of life in Viharas in closer proximity to people for their service and welfare not to speak of the adversarial proximity with some grudging admiration for activities of social service by the Christian and even Jewish seminaries. The Sufis were inclined to pick up relevant elements from here and there in the cultures of alien lands as long they could serve the purpose of spreading the message of Prophet in conformity with the evolving Islamic Sunna. They were guided by the divine wisdom contained in the Quran, 'to be interpreted with increasing insight'. The doctrine of the Last Judgement; the assertion that, 'God loves them (mankind) and they love Him'; the strictly regulated life of Prophet - all provide the strong spiritual anchor of Sufism. Another fundamental concern in Islam has been Tawhid, "There is no deity but God" which thinker Junayd Baghdadi (d-910) had tried to explain, "Recognising God as He was before creation". The two aspects - God and creation - as one Immanent reality, Wahdat al-Wujud, were further reinforced in terms of Tawhid to mean that there is nothing existent but God.

Though Sufism had certainly been developing a distinct character by the twelfth century, great Sufi saints in the length and breadth of the vast Islamic empire were not rigidly disposed to fine tuning the nuances of the faith when under compulsions of commandments of the kings and what would work with the people. The Sufi influence in India came from north west when Shaikh Ali Hujwairi (d-c1079), widely known for his work Kashf al-Mahjub, settled in Lahore - his Shrine has been attracting a constant stream of devotees professing all faiths. Shaikh Muinuddin Chishti (1142-1236) estabilished himself in Ajmer after Shihabuddin Ghori defeated Prithvi Raj. Shaikh Bahauddin Zakaria(1176-1271), after blessing by Shihab al-Din Suhravardi of Baghdad, came down to Multan. The Sufi orders, silsilas, mentioned to be 14 in the Ain-e-Akbari had a vast expansion with the consolidation of Muslim rule in India - the most important being the Chishtia, Suhrawardia, Naqashbandia, Qadria, Firdausia, Shattria among the 'orthodox' and the Qalandars and Madars among the 'unorthodox'. With passage of time, many Sufi saints like Shaikh Muinuddin Chishti, Hazrat Ali bin Uthman - popular as Data Ganj Baksh - Shaikh Bahaauddin Zkaria, Shaikh Fariduddin Ganj-e-Shakar (1175-1265), Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya, Hazrat Mian Muhammad Mir (1585-1655) have become the most adored ones with their tombs becoming places of pilgrimage and huge popular fairs. While most of the Sufi saints shunned the seats of power and kept a safe distance from the rulers even when sought after, some others were known to play politics and influence peddling. There were trying situations during struggles of royal successions which got murkier and bloodier in history and Sufi leaders had to pay for their proximity to the losers. Dara Shakoh, the crown Prince designate by Shahjahan was not destined to be 'the Sufi King of Hindustan': and his spiritual guide and friend Sarmad, the naked Sufi poet, became Mansur of India and Prince among martyrs of faith.

The Sufism has indeed left a strong imprint not only on the socio-religious history of India but has also made lasting contribution in the realms of literature, arts, philosophy, music, crafts and other dimensions of national life. The Sufis were, in their own way, the harbingers of 'soft power' of globalisation and even the dialogue of civilizations in their times. The concept of composite culture of the sub-continent can be traced to doors of the khanqahs of the Sufis. The Sufi centres encouraged and provided for education and learning among the masses.The message of social equality, particularly against the curse of the Caste system in Hinduism was never conveyed so loud and clear in theory and practice as by the Sufi derveshes. They were often advocating the causes of the poor and the deprived sections of society. Being tireless travellers, the Sufis propagated bridging of narrow cultural divides. The twin towers of strength of Sufis were their aquida ie faith and ishq that is love - both for Allah and his makhluq - creation. To quote Hazrat Bayazid Bistami:

If you aspire communion with God / Be kind, generous and just to your fellow beings.

If you desire effulgence like the dawn / Be magnanimous to all, like the sun.

As for India, the partition of the country on the basis of an untenable communal ideology has involved the challenging task of renewal of values of communal harmony not only in in India but tellingly in predominantly Muslim Pakistan too - what the Sufis had tenaciously worked to accomplish. No wonder that the studies in Sufism have been increasingly encouraged in higher academic institutions and there is tremendous interest in the movement epitomising Majma-al Bahrain - Mingling of Two Oceans - Hindu and Muslim mystical ideas. The most palpable and profound impression of Sufism has been in literature of various Indian languages. The Sufi impulses have inspired the sublimest poetry with the celebrated saints preferring the local regional tongues for the most intimate communion about the universal divinity for all. The poetry of Ameer Khusrow, Baba Farid, Kabir and many more in Bhakti-Sufi tradition, not to speak of later Urdu, Hindi, Sindhi and Panjabi poets but also the idiom of progressives, indeed draw upon the core of the span and spectrum of the rainbow of India's Bhakti-Sufistic heritage.

According to eminent Urdu writer - thinker Ali Jawad Zaidi, the Sufis were indeed the pioneers in promoting Urdu using sayings - malfuzad - and Dohas to serve their missionary purposes. Sheikh Gangoi was a great poet of Braj Bhasha and also wrote in Hindi under the pen-name of Alakhdas. The echo of Sufi sayings and ideas is apparently distinct in hymns of Namdeva (1270-1350) of Marathwada. Kabir (c1399-1515), the weaver, has been rightly hailed as one of the most popular saint poets of India who wove magic in a simpler language to convey his forthright views on the prevailing socio-religious hypocrisy. The celebrated Hindi critic Acharya Hazari Prasad Diwedi has commented that, "Kabir had a rare and powerful grip on language...he had no peer in the use of to satire and irony...he hit (hypocrites) so hard in simple and chaste words that the target had no choice but flee in surprise...he indeed holds a unique position in the millennium of Hindi literature". Kabir says it all in his inimitable way:

Main kahta hun ankhi dekhi / tu kehta hai kaagaz ki lekhi

I speak of what I observe; you are quoting the writing on a piece of paper.

Among other saint poets in the fraternity of sufis, mention must be made

of Sant Dadu Dayal, Mallookdas, Dharam Das and the Prem Marg - love path - saints like Kutuban of Jaunpur, Mamjhan who wrote Madhumalati, Malik Mohammad Jaysi of Padmavat fame, Usman of Ghazipur etc. The land of Sindh, the seat of the earliest civilization on the banks of the legendary river which has imparted its name to the country, had its own intimate interaction with Sufism with the mystical domain of Sindhi poetry led by Qazi Qadan (1463-1551) followed by Shah Abdul Karim (1536-1623) known for his beautiful Baits, Shah Inat (c1623-1712), Shah Latif (1689-1752) famous for long wail of firaq - separation - in Risalo and Sachal Sarmast (1739-1812) who composed beautiful kaafis and Ghazals. Sindhi sufi poets were also great integrators and remained above any narrow sectarian and religious divisions - Shah Abdul Latif says: Bestowal is regardless of caste and creed, all who seek may obtain Him!

It was however,among people of the land of five rivers, always fertile for fresh and healthier all embracing ideas since ages, that Sufism was received with enthusiasm and deeper commitment. Shaikh Baba Farid should be considered among the major figures of renaissance in India whose spiritual insights remain valid even after eight centuries. The inclusion of Farid's evocative hymns and shlokas in the Granth Sahib compiled by Guru Arjan Dev has been a subtle point of reference in the realm of theology in India apart from their literary merit. In the words of Prof Attar Singh, "By admitting these verses into the Guru Granth Sahib, Guru Arjan Dev no doubt added a new dimension and lent them universality by juxtaposing them with religious writing drawn from other traditions." It is interesting to study the medieval Bhakti, Sufi and Sikh poetry to discover that they were all 'struggling against the deadening enslavement to orthodoxies of religions'. Prominent Punjabi Sufi poets including Sultan Bahu (1629-1691), Bulle Shah (1681-1757) and Ali Haidar (1690-1785), following the path shown by Farid, had reacted sharply against indignities based on religion at the behest apparently of Naqashbandis. Even though the process dialogue initiated by the Sufis had a set back in the background of historical circumstances of bloody wars of succession between the Mughal Princes, the frame work of reference for reconciliation had got registered for ever in the minds of a vast majority of people.

What is the contemporary relevance of ideas propounded by the Sufis of sub-continent? Annie Zaidi, a young journalist, has narrated in a charming essay titled, A Little Bit Wild in the Faith Department in her recently released book how generation of young people like her in India - in South Asia as a whole - are irresistibly drawn towards Sufistic ideas and symbols, particularly the music and poetry popularised by Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan's clan and Rabbi Shergill's evocative, Bulla Ki jaana main kaun? not to mention legions of popular singers of of folk tradition and Bhajan circuit led by Hans Raj Hans. The films have also immortalised gems of Sufi poetry. The Deras of different persuasions are comfortable accommodating the Sufi values and some of them like the Radha Soami Satsang Beas have published scholarly commentaries and translations on the works of Sufis like Sarmad, Shaikh Farid, Bulleh Shah etc. The famous Sufi shrines are receiving devotees - expectant visitors - in hundreds of thousands. The state machinery would also appear to be well disposed towards the Sufi heritage in the region. The historians in India have no credible theory to explain mass conversion of people to Islam in India. Harbans Mukhia refers to an essay of 1952 by Prof Muhammad Habib stating that caste oppression might have been a crucial factor among the lower strata of the society. Interestingly, the largest conversions have taken place between mid 19th century and 1941 when Sufism had been in decline due to internal weaknesses. Some Islamists of the Fundamental kind, particularly the Deobandis, likened to Saudi Wahhabis, have been critical of several Sufi practices including the adoration of tombs. It is sadly true that all the faiths proclaim to unite people but every faith has its share of sharply divisive - many times violent - controversies.

In Sufi poetry, the sojourn of a person in the world has been symbolised as musafir - a wayfarer - and a saudagar - a trader - while the world itself is called a Sarai - inn - in the way where traveller / trader has a short stay. Bulleh Shah wishes to travel far, too far to find the Invisible Beloved:

Bindraban me gaooa charae / Lanka charh ke naad vajae

Makke da Haji ban aae / vahva rang vatai da

Hun kisto aap chhapai da!

You graze cows in Brindaban / You sound victory horn in Lanka

You change colors so wonderfully / From whom are you hiding now!

The 21st century had promised to be different for humanity but a decade later the world finds itsef deeply enmeshed in the ancient conflicts of the religious kind - fancifully termed 'clash of civilizations' - with weapons of total annihilation still proliferating while the life sustaining precious natural resources and ecology are fastly dwindling threatening life again in toto! One intuitively turns to pray with words of the Sikh scripture Guru Granth Sahib,

Jagat jalanda raakh le, apni kirpa dhar

Save this scorched earth, O Lord, with your bountiful mercy

____________________________

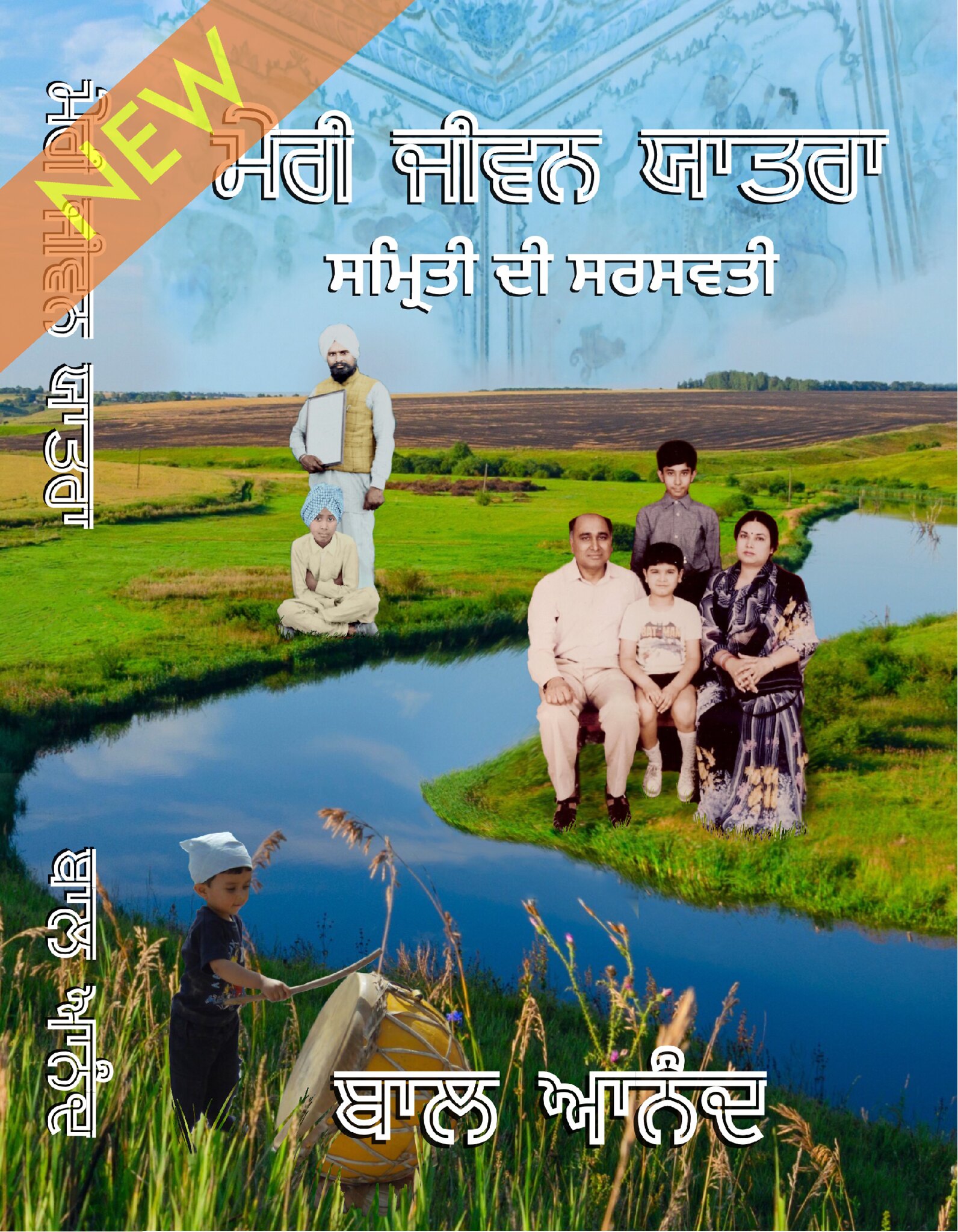

Author's father striking notes of Sufi-istic harmony and innocence

Circa, 1952

Circa, 1952

____________________________