This article was published in the monthly magazine Identity, in the January 2014 issue.

The most interesting origin and bafflingly complex evolution culminating in the art and craft of ‘writing a letter’ would seem to embrace the entire history of the civilisation of humanity. The story telling, songs, festivals and rituals were the earliest oral attempts by our ancestors to preserve and underline their traditions and memories. The beginning of means of disseminating information to those located at distances might have included, ‘the marking of stone, indents of clay, knotted lengths of cord, scratching of plates of metal and wood, etc.’ The development of writing is understood to have taken place sometime after 3500BC. Sumerian writing had pictograms and ideograms for the start. Scribes were soon busy in simplifying the system, using symbols to represent sounds and syllables on tablets of wet clay to be baked later. This writing was called Cuneiform, from the Latin word cuneus, meaning a wedge.

The ancient Egyptians were able to produce a large body of what could be termed as literature. An extract from one of the oldest book of letters containing instructions to his son by the Vizier Ptah-hotep to the Pharaoh, who lived about 2450BC, would seem to ring tellingly so true about the administration of state even today:

“Do not let your heart be puffed up because of your knowledge… If you, as leader, have to decide on the conduct of a great many people, seek most perfect manner of doing so, that your own conduct may be blameless… Be active, doing more than what is commanded. Activity produces riches but riches do not last when activity slackens… Do not rebuff petitioner before he has said what he came for. A petitioner likes attention to his words better than fulfilling of that for which he came…”

The timelessness and universality of letter writing has indeed imparted this form of writing a rare uniqueness in terms of its historical, cultural and literary dimensions. By the 18th century, letter writing had become so common in the West that ‘one of the first prose narratives to be considered a novel, Samuel Richardson’s Pamela was composed entirely of letters of a daughter to her parents, and the epistolary method lent that novel what realism it possessed.’ The accomplishment in letter writing has been indeed considered for the last two centuries to be the finest attribute of a highly cultivated mind. The best minds in India’s struggle for freedom - from Assadullah Khan Ghalib to MK Gandhi including Maulana Azad, Jawaharlal Nehru, RN Tagore, Sardar Patel, Sarojini Naidu, Bhagat Singh - all have left behind tons of 24 carat golden letters for historians and ‘aam Indian aadmi/aurat’ as their authentic legacy.

The sharp decline in the practice of letter writing in the beginning of the 21st century, in the wake of the revolution of the new technologies of communication, would seem ‘to constitute a cultural shift so vast that historians may divide time not between B.C. and A.D. but between the eras when people wrote letters and when they did not.’ The historians in general, and literary chroniclers in particular, have depended the most on the written references and the personal letters fall in the special category as evidence of how our ancestors once lived, loved, argued, thought and above all expressed their innermost feelings. The untouchables in India and slaves in the world over were often illiterate by the perverse moral prescription of the caste system and the enacted laws that threatened them with death. The epistolary tradition historically belongs to free people - that means the upper castes land owning groups in India and the white people of property in larger parts of the world. The authentically written record is indeed the most precious instrument to illuminate the past, present and future.

I have had the good fortune to be most rigorously tutored in writing letters and luckier to be recipient of the most loveable responses from respected elders, distinguished wielders of the pen and so many sincere friends. I can vividly recall how during my fourth class in 1952, my father, himself taught in the rigorously classical tradition by his scholarly grandfather, had guided me to write a letter in Punjabi to the husband of my BhuaJi - paternal aunt - who was serving in the military. I had to write letters to my father who served the Government of Punjab for about a decade between 1956-66 and a teacher uncle who always preferred to be posted at distant places. I was myself away from home for about 5 years till 1971 both as a student and as a lecturer at the college. Then the career in Indian Foreign Service till 2004 made me a compulsive writer of letters during my postings to nine different capitals of the world. Most of my letters were in Punjabi addressed to friends who also replied in elegant Punjabi. The letters to my most revered school teacher who taught me English were exchanged in English - I think that both of us felt mutually proud of each other over our proficiency in Firanghi Bhasha!

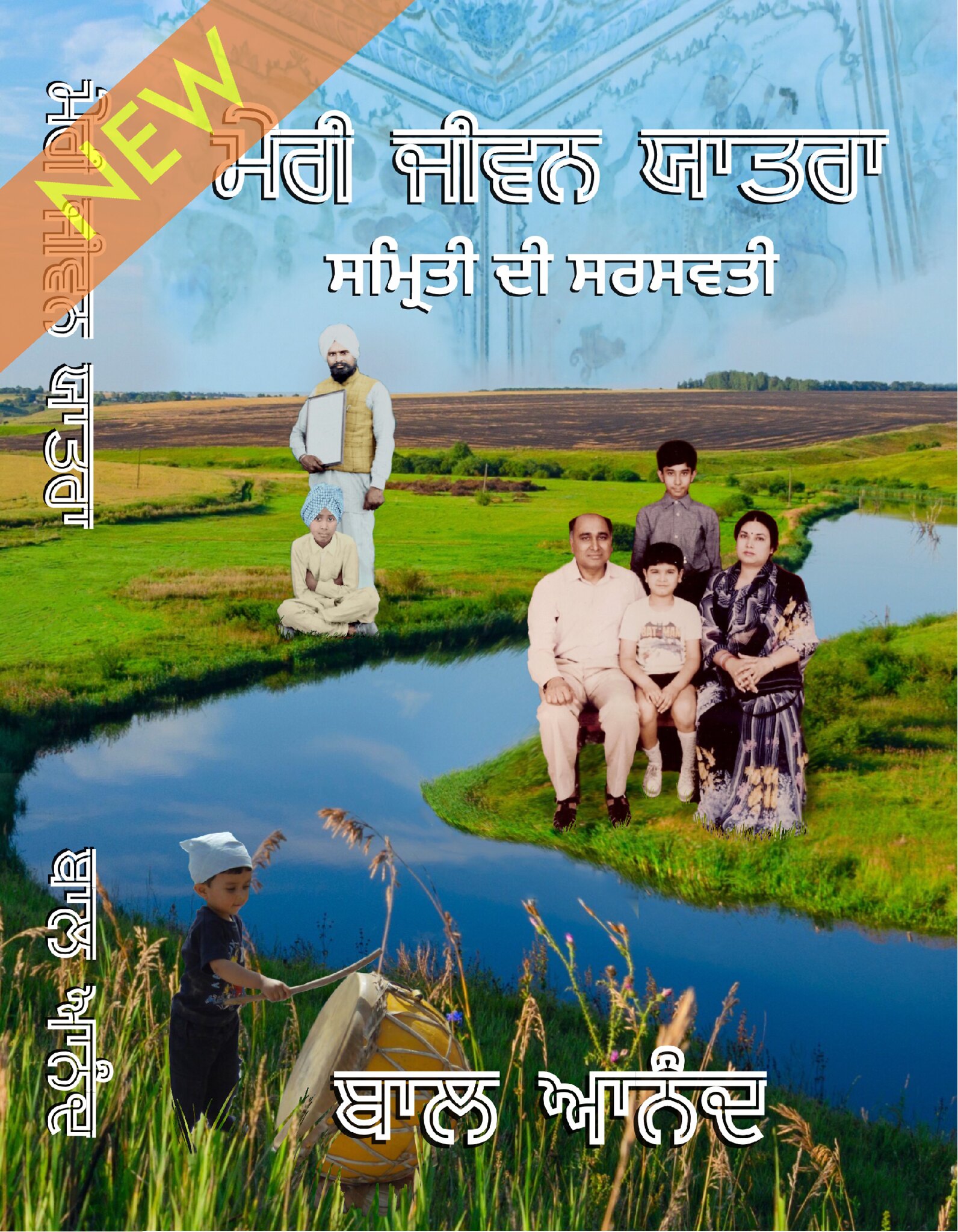

When I retired in 2004, I felt a strong desire that the select letters written and received, originally in Punjabi, and all meticulously preserved by me including copies of my own since the availability of the photo copying facility, deserved to be shared with the Punjabi knowing readers. My resolve was strengthened by the pleasantly surprising discovery that Prof Pritam Singh, the most distinguished scholar and “a teachers’ teacher” of Punjabi, had forwarded my letters to him to the Punjabi Sahit Academy, Ludhiana for preserving them for their literary merits! The task to get one’s maiden book published in Punjabi on its self-proclaimed literary merits is, however, to quote two English proverbs learnt in school, amounted to an ‘uphill task’ or even a ‘wild goose chase’. My perseverance coupled with sincere encouragement by the eminent Punjabi dramatist Prof Charan Dass Sidhu - I had come to know him only during my period of retirement - put me on the right track. Shilalekh, a publishing house patronised by Amrita Pritam and my school-time poet-hero, Krishan Ashant staked their reputation to publish this anthology of original letters, penned during 1967 to 2009.

This anthology titled, ‘Sukh Sunehe - Epistles of being O.K.’, covering 208 pages, has 154 letters to and from 23 persons. There are 52 letters exchanged with their replies by Prof Pritam Singh, in his chaste and inimitable style characterised by clarity and stern sweetness about the tasks to be accomplished. There are 14 letters exchanged with Prof Sat Parkash Garg (1937-1996), a soulmate friend and colleague of the vintage of my lecturership in the Govt. College, Bathinda. In his letter of 23rd January ’96 he had written, “I anxiously await your letter… when are you coming - we shall definitely meet, if I would still be alive…”, and that was not destined to be; he passed away on the operation table undergoing heart surgery when I was on my way to India! The third main series of letters is with Jang Singh Gill who belongs to my village. He was my class fellow in the initial two years of school and has retired as a competent and popular science teacher in the Govt. Secondary Schools. Jang Singh has been instrumental in graciously keeping my umbilical link alive with my roots. The letters by Ajmer Singh, a twelve years senior distant cousin from my mother’s side, poetically recapture the most creative and enjoyable atmosphere of early 1950s in the Ripudaman College, Nabha. There are intimate literary letters exchanged with prominent writers of Punjabi including Balwant Gargi, KS Duggal, Gurbachan Singh Bhullar, Dr S Tarsem, KL Garg, and Dr SS Johl.

|

| 21-12-2013, Sukh Sunehe released at Sahit Sabha, Malerkotla L to R: KL Garg, author, Balbir Madhopuri, Dr S Tarsem, Jagir Singh Jagtar, Dr Rubina Shabnam, & Sh Mittar Sain Meet |

Sukh Sunehe was released on 21st December at an impressive literary function organised by the Sahit Sabha, Malerkotla. The erudite young poet and critic Kamal Kant Modi presented a competent paper on the book highlighting “its literary character and its being an extraordinarily authentic document of the four decades of the period of these letters.” It was indeed a soulful delight for me that several of my dear and distinguished class fellows including eminent Punjabi satirist KL Garg, Prof AS Sidhu, JS Gill, industrialist Vinod Mehra - all my intermediate class fellows in 1959-61 in the Govt College, Malerkotla, were also in attendance. It was a rare personal privilege for me that many dedicated senior progressive literary activists including Jagir Singh Jagtar, SohanLal Bansal, Naz Bharati, Tarlok Singh Rai, Mittar Sain Meet had graced the function. Malerkotla has indeed significantly emerged on the horizon of Punjabi literary scene because a dedicated scholar and multi-talented writer of the stature Dr S Tarsem has made a choice making his nest in this historic city. The day - the shortest in the northern hemisphere of the planet - was his 72nd birth day and his latest book of literary profiles, ‘Sagar Tet Challan - Ocean and the Waves’, was released and also followed by an animated discussion.

Many devoted practitioners of the art of letter writing have been feeling gravely concerned that the new age of instant communication technologies might soon herald the end of traditional type of letters. There are also still incorrigible optimists, including myself, who are convinced that letters as ‘a dialogue of the soul’ can neither be replaced, nor is it going to disappear - ‘no other form of communication yet invented provides you to put your essential self on paper…’ I think that by putting this anthology of letters, written originally in Punjabi, in the public domain I have done my duty to my mother tongue… before the hand crafted letters become a thing of the past.