* Published in 'Balbir Madhopuri di Svai-jeevni Chhangia Rukh da Sahitak -Samajik Mulankan' - a socio-literary evaluation of Balbir Madhopuri's autobiography

An Autobiography By Balbir Madhopuri

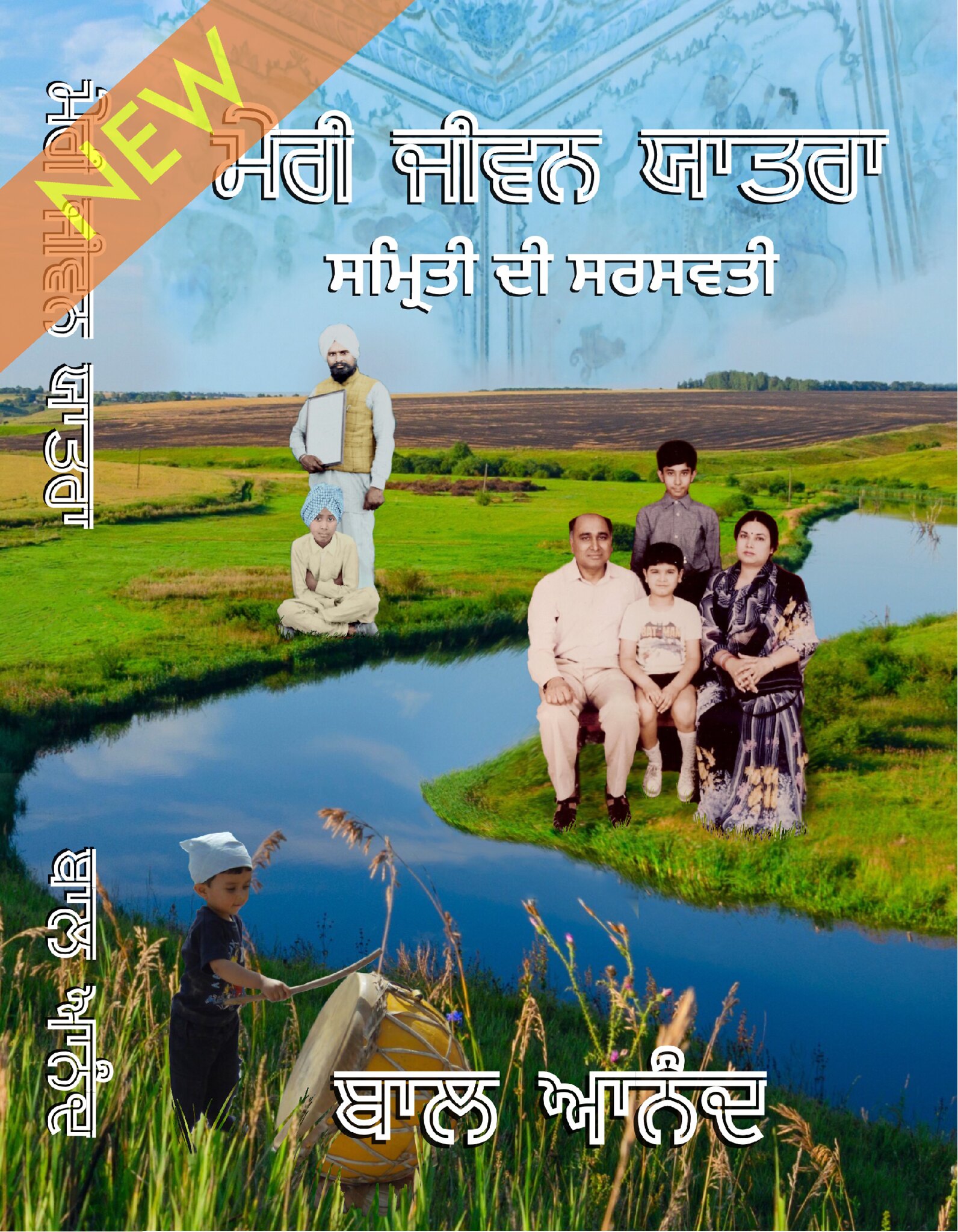

A Critical Appraisal and an Overview : Baal Updesh Anand

This bare, bold and tragically-touching beautiful literary creation of the autobiographical kind, first published as a book under the above title in January, 2003, has been receiving a wider appreciative acclaim of the select top critics and the limited but cultivated readership of the Punjabi literature. The fact that the book has already run into two hard back and three paper back editions is indeed a great news which should cheer up all those who are always complaining about the vaporous nature of the readership of Punjabi language. The poetic title of the autobiography – Madhopuri made his literary debut with an anthology of poems titled, ‘A Tree of Desert’ (1992) to be followed by ‘The Smouldering Underworld’ (1998) – could, perhaps, be faulted by a Botanist but it does pinpoint the deep deprivations and corroding compulsions encountered by an Indian born an Untouchable in a landless family in rural India – here in a comparatively progressive State of Punjab – even decades after Independence and adoption as law of the land of the noblest Constitution crafted by Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, the greatest thinker-emancipator in the history of mankind.

It may indeed be educative to note how the Untouchables have undergone significant transformations since the scriptural Shudra / Achhuth / Bahishkrit; socio-economic Depressed classes; Gandhian Harijans; Secular and constitutional Scheduled Castes till the contemporary nomenclature of the Dalits, echoing daring defiance, political protest, solidarity with all the oppressed in the world, particularly the Black in the U.S.A. It is mainly since the sixties of the twentieth century that, in practical parlance, the word Dalit becomes an explosive catchword for social, cultural and political revolutionary movements launched by untouchable castes, essentially the Mahars, in such expressions as “Dalit literature” and “Dalit Movement”. The period was to witness an eruption of many luminous minds – hitherto branded ‘the lowest’ in the Hindu social dispensation – in powerful literary outbursts challenging the social & cultural value system. The ‘Dalithood’ has signalled its arrival as an ideology: its literary reach has been spreading to all the languages in India. While the poetry and short stories with the ‘Dalit’ themes have been in the forefront, it is the Dalit autobiographies which have created waves and with their translations in Hindi and English; they have led to literary discourses at not only the national but international level also. The Dalit autobiographies ought to be studied ‘as an authentic source of Dalit Cultural identity as well as an attempt to re-inscribe Dalit identity in positive, self-assertive terms.’

In the opening chapter, ‘The Rationale of a Dwarfed Tree’, Balbir Madhopuri is disarmingly candid in explaining the idea of the writing of this autobiography and the genesis of this book of deeply personal and intensely closer encounters and experiences of the life of the ‘Dalit kind,’ Intriguingly, he was ‘provoked’ – rather than inspired – and even challenged to attempt a better piece of writing than the one he was belittling, elaborating on the pains, privations and the dehumanizing realities attendant upon the Dalits. He further adds how the real-life portrait, ‘My Grandmother – a History’ was first published in the eminent Punjabi monthly of the yester-years, Aarsi, in Dec., 1997 by the generous patriarch publisher Bhapa Pritam Singh who also promised to publish the full autobiography. Madhopuri also acknowledges that the words of encouragement and appreciation by the well-known Punjabi writer Ajit Cour became a source of inspiration for the 42 years old budding poet-author who, although a lower – middle rung official of the Govt. of India, started receiving recognition in the ‘big-complex- literally-world’ of the capital of the country as an author with a ‘distinct point of view’. The author, in the opening remarks of the book, has painstakingly pointed out how he had to, as if, “unfold” his “self”, layer by layer; enter into a deeper dialogue with “self” : searching for the ‘identity’ of the ‘self’ and attempt to make up his mind to ‘write down all that’. He further admits, “Believe me, when I would read what I had myself put down on paper, tears would trickle down my eyes and I would feel choked”. The author confesses that he had to pause a while, reading what had been written, thinking ‘what horrible indignities my forefathers must have endured!’ A few more autobiographical articles were published later in the other important literary magazines of Punjabi – more accolades from the leading Punjabi writers followed, ‘it is nice that you are writing, focussing on this topic i.e. Dalithood – so far it has been an ‘unploughed’ field (in Punjabi)’. There were also a few doubting Thomases suggesting that it was, perhaps, too early in life and that there were not enough literary or personal attainments justifying a full length autobiography. The dilemma of all these factors coupled with sheer shortage of time, according to the author, caused a delay of almost five years for the publication of the book under reference.

The author states in clear terms that the events elaborated in the autobiography are ‘one hundred per cent true’ and even the names of characters have been retained in their popular nomenclatures – ‘imagination has been brought into play, more to carry forward the sequence of conversations and to maintain the contexts’. The author further underlines that he did not to make any special effort to ‘build up the typical atmosphere of the rural life (of Doaba region of Punjab) and that the purpose of writing the autobiography had become quite clear in his mind – ‘to make the contemporary and the generations to come to be fully aware of the stark realism of the heritage of the dire poverty and excesses at every step in the lives of the Dalit community’. The author wonders why the progressive intellectuals have mostly chosen to remain aloof and do not raise their voice against the ‘conspiracies’ against the Dalits. He describes the writing of the autobiography ‘as one of the bricks in the foundation of the edifice of the structure of efforts to make the socio-economic transformation a reality’.

It will be more purposeful to attempt an overview of the text of the book before discussing its literary merits and limitations. The opening chapter titled, ‘The Land of my Birth – Madhopur’ introduces the reader with the geography, topography, folk history and the overall environment of the region situated in the catchments area of river Beas joining the Sutlej at the edge of District of Kapurthala. The author takes the reader on a socio-economic survey trip of Madhopur in District Jalandhar with the help of verifiable official documents and other land marks, ‘the first double-sided village well was dug up in 1800 A.D. using 419811 bricks!’ The background on the social divides and the various land legislations denying the basic rights to land ownership to the untouchables in the community have been elaborated. The author’s comments on the unjust social system have been elaborated. The author observes that there is no comparable example in the world of an unjust, discriminatory and unequal social system prevalent in India but also refers to the emergency of leaders with enlightened vision – he quotes Karl Marx, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar and Jawaharlal Nehru in the same paragraph. He also refers to the stellar role of the local Dalit hero, Babu Mangu Ram Mugowalia, as a revolutionary for the cause of social justice. He concludes the first chapter on a hopeful note – ‘social change demands dedication and courage from all the segments of society; there is a dire need of rational outlook in life; the Dalits are keen that the entire country becomes prosperous.’

The chapter titled, ‘A Thick Writing on a Blank Paper’ gives a graphic account of the situation of the Dalit community living on the periphery of the village called ‘Chamarali’ vis-à-vis the interaction with the upper caste ‘Jatt’ community. The scene of the distribution of ‘Prashad’ in the Gurudwara made a mockery of all the subtle teachings and the tall claims of the practice of equality among the Sikhs in a Punjab village. The author has exactly reproduced the piercing degrading remarks laced with un-uttered abuses hurled at the low caste children by the Sikh priest. We are also introduced to interesting characters like Gurdas claiming ‘possession’ by the Peer (dead Muslim Saint) and a few members of the author’s family including his father, Thakar Das. There is the most memorable and touching incident when the author, as a small child, is hung up side down in the well by his father to frighten and forbid him against eating the soil. It was the intervention of his mother which saved the day for the author. There are references to the utterly unclean food and drinks in the home including the white worms infested gur i.e., jaggery used to make tea. The lack of proper protective clothes in the winter season for the children of the Dalit community has also been described with wit and pathos. The description of attack of the locusts in the village and the experience of the author (he was then studying in the second grade in the school) of eating the fried locusts are indeed touching! The next chapter, ‘The Story of the Cracked Mirror’ presents the reader with a rare account of the verbal clash between a high caste Jatt and Phuman, a tenth class student of the Dalit community and a cousin of Madhopuri. The shortage of household requirements including the food grains in the Dalit homes have been vividly described explaining the resultant miseries. The author’s childhood nickname, ‘Good’ ie ‘ a male doll’ also tells the readers his humiliating experiences of ‘Bhitt’ ie untouchability, an ‘untranslatable’ word indeed, and also refers to the severe skin disease common among children of the untouchables.

The chapter entitled ‘The Flowers of the Wild’ presents an interesting picture of the female characters in the author’s family including the strong minded and colourful, Grand-Mother. During discussions in the family, the stories of Brahamanical mythologies including those of strange-bodied gods are ridiculed. The glorification and sanctity of the vegetarianism are also challenged, quoting counter historical and other sources. The tensions in the village, particularly during the difficult period of heavy rains, are described by the author in a very interesting manner. The author also touches upon the acute financial difficulties faced by his family and the unfulfilled hope that his maternal uncle who is a high official would be able to help the family in getting a regular job for the author’s father or his elder brother. The author returns to give to the reader a more intimate portrayal of his grand-mother, particularly her fondness in earlier times for the cattle meat. The pent up feelings of the author’s father find bitter expressions: “They worship the cattle…we are considered worse than animals…they say, keep off, you will make us unclean!” The chapters titled, respectively, ‘Travellers of Thorny Paths’; ‘Sun Gazing through the Clouds’; ‘Our House, Home of Sorrows’; ‘Brahama’s Empty Vicious Circles’; ‘Hunger and Thirst have no Caste,’ The tangle of Kinship’; ‘The Drought in Rainy Season’ bring out most realistically the pains and sufferings of the author’s family viewed both from the angles of an innocent child and a literary artist. The image of the IAS maternal uncle looms large at several places – as a role model and also for his inability in bailing out the family.

The chapter ‘The Banyan Tree’ provides a live portrayal of the most popular place for the community life of the Dalits of the village. The shelter of this big-ancient tree was even used to carry out the various small time professions including plying the handlooms. The author was studying in the 10th class when this banyan tree was cut down by the order of the village panchayat and it was indeed the end of an era and a whole world came down crumbling with the tree. Symbolically, the grandmother of the author did not survive this tragedy. The chapter titled, ‘A River Flowing in the Desert’ describes at length an extremely good natured family of the Jatt caste of Baba Arjan Singh which remained the best of friends of the author’s family till their last – “now when I recall the genuine affection of this Jatt family soaked in all the pores of my body, I feel that he (Arjan Singh) was a river in the desert of the life of our family; it did result in sprouting of some greenery”.

The chapter of the book titled, ‘Hatred with My Name’ recounts several bitter experiences of the author during the period of his early youth. He is frank and bold in stating that he felt ashamed over the large size of his family. He could even dare to tell his mother that he did not need any more brother or sister and that he felt terribly shy while carrying the younger sisters around. When the mother somehow mentions the author’s remarks to his father, his ringing comment needs to be quoted in original, “Saala Angrezan da, laapia mattan den…tere kahe main raddi hoke ghar bah jaaman”, translated loosely, ‘you, brother-in-law of the English, you dare advise me…do you think I should become a ‘wasted’ good for nothing fellow, sitting at home on your suggestion’. The author mentions that he wanted to tell that the small house was so overcrowded with ten persons including several animals under the same roof during the winter. The author refers to the environment in the college in 1972 when the students had resorted to a 39 days’ strike. During the studies in the college, he became deeply interested in the progressive literature and came closer to the Community Party of India in 1974-75. The poems written by him expressing anti-American sentiments were regularly published in the CPI Daily Nawan Zamana and other magazines and he felt convinced that India also needed a revolution like the Soviet Union, ‘ with economic equality established with some magic and where there were no caste distinctions in the society’. He also joined the college for doing post-graduation in Punjabi in Jalandhar and came into contact with sympathetic teachers and also became friendly with the militant poets like Pash and Sant Ram Udasi.

The author got a job in the Food Corporation of India in 1978 and continued his involvement with the activities of the Union. He was, however, to discover soon the narrow mindedness and weaknesses of character of many so-called progressive colleagues. The next turning point in the life of the author was his selection for a Class-II non-Gazetted Officer in the Press Information Bureau in 1983. The rise of the extremists Khalistani movement in the Punjab deeply upset him. The chapter titled, ‘Literature and Politics’ contains telling comments describing the situation during this dark period. The family of the author was immensely relieved when he was transferred to Delhi in 1987. The next two chapters describe respectively the author’s accidental encounter with the terrorists and also a hypocritical Guru in Delhi. The last chapter of the book, ‘The Curse of being a Tenant’ describes all the attendant difficulties of renting an accommodation in Delhi – with the caste factor also playing a role for the author.

The two hundred page book by Madhopuri is certainly a landmark in the category of autobiographical writing in Punjabi literature. The eminent novelist Gurdial Singh has earlier written powerful and sensitive prose describing the trials and tribulations of the marginalized people in rural Punjab. Madhopuri has, however, brought alive the physical pains and the deep sufferings of the souls of those at the bottom of the caste divides – an area which has hitherto remained almost untouched in Punjabi literature. It is hoped that Madhopuri’s autobiography would soon be available to a wider spectrum of readers in translations in Hindi (already published by Vani Prakashan, Delhi) and English. To capture the exact nuance of lyrical prose in the typical dialect of the Punjabi of the Doaba would indeed be a challenge for the translators. A Dwarfed Tree – an autobiographical diagnostic of Dalithood - certainly needs to be studied for the bigger issues and larger perspectives of the social and economic scene in India in the beginning of the 21st century.

It may indeed be educative to note how the Untouchables have undergone significant transformations since the scriptural Shudra / Achhuth / Bahishkrit; socio-economic Depressed classes; Gandhian Harijans; Secular and constitutional Scheduled Castes till the contemporary nomenclature of the Dalits, echoing daring defiance, political protest, solidarity with all the oppressed in the world, particularly the Black in the U.S.A. It is mainly since the sixties of the twentieth century that, in practical parlance, the word Dalit becomes an explosive catchword for social, cultural and political revolutionary movements launched by untouchable castes, essentially the Mahars, in such expressions as “Dalit literature” and “Dalit Movement”. The period was to witness an eruption of many luminous minds – hitherto branded ‘the lowest’ in the Hindu social dispensation – in powerful literary outbursts challenging the social & cultural value system. The ‘Dalithood’ has signalled its arrival as an ideology: its literary reach has been spreading to all the languages in India. While the poetry and short stories with the ‘Dalit’ themes have been in the forefront, it is the Dalit autobiographies which have created waves and with their translations in Hindi and English; they have led to literary discourses at not only the national but international level also. The Dalit autobiographies ought to be studied ‘as an authentic source of Dalit Cultural identity as well as an attempt to re-inscribe Dalit identity in positive, self-assertive terms.’

In the opening chapter, ‘The Rationale of a Dwarfed Tree’, Balbir Madhopuri is disarmingly candid in explaining the idea of the writing of this autobiography and the genesis of this book of deeply personal and intensely closer encounters and experiences of the life of the ‘Dalit kind,’ Intriguingly, he was ‘provoked’ – rather than inspired – and even challenged to attempt a better piece of writing than the one he was belittling, elaborating on the pains, privations and the dehumanizing realities attendant upon the Dalits. He further adds how the real-life portrait, ‘My Grandmother – a History’ was first published in the eminent Punjabi monthly of the yester-years, Aarsi, in Dec., 1997 by the generous patriarch publisher Bhapa Pritam Singh who also promised to publish the full autobiography. Madhopuri also acknowledges that the words of encouragement and appreciation by the well-known Punjabi writer Ajit Cour became a source of inspiration for the 42 years old budding poet-author who, although a lower – middle rung official of the Govt. of India, started receiving recognition in the ‘big-complex- literally-world’ of the capital of the country as an author with a ‘distinct point of view’. The author, in the opening remarks of the book, has painstakingly pointed out how he had to, as if, “unfold” his “self”, layer by layer; enter into a deeper dialogue with “self” : searching for the ‘identity’ of the ‘self’ and attempt to make up his mind to ‘write down all that’. He further admits, “Believe me, when I would read what I had myself put down on paper, tears would trickle down my eyes and I would feel choked”. The author confesses that he had to pause a while, reading what had been written, thinking ‘what horrible indignities my forefathers must have endured!’ A few more autobiographical articles were published later in the other important literary magazines of Punjabi – more accolades from the leading Punjabi writers followed, ‘it is nice that you are writing, focussing on this topic i.e. Dalithood – so far it has been an ‘unploughed’ field (in Punjabi)’. There were also a few doubting Thomases suggesting that it was, perhaps, too early in life and that there were not enough literary or personal attainments justifying a full length autobiography. The dilemma of all these factors coupled with sheer shortage of time, according to the author, caused a delay of almost five years for the publication of the book under reference.

The author states in clear terms that the events elaborated in the autobiography are ‘one hundred per cent true’ and even the names of characters have been retained in their popular nomenclatures – ‘imagination has been brought into play, more to carry forward the sequence of conversations and to maintain the contexts’. The author further underlines that he did not to make any special effort to ‘build up the typical atmosphere of the rural life (of Doaba region of Punjab) and that the purpose of writing the autobiography had become quite clear in his mind – ‘to make the contemporary and the generations to come to be fully aware of the stark realism of the heritage of the dire poverty and excesses at every step in the lives of the Dalit community’. The author wonders why the progressive intellectuals have mostly chosen to remain aloof and do not raise their voice against the ‘conspiracies’ against the Dalits. He describes the writing of the autobiography ‘as one of the bricks in the foundation of the edifice of the structure of efforts to make the socio-economic transformation a reality’.

It will be more purposeful to attempt an overview of the text of the book before discussing its literary merits and limitations. The opening chapter titled, ‘The Land of my Birth – Madhopur’ introduces the reader with the geography, topography, folk history and the overall environment of the region situated in the catchments area of river Beas joining the Sutlej at the edge of District of Kapurthala. The author takes the reader on a socio-economic survey trip of Madhopur in District Jalandhar with the help of verifiable official documents and other land marks, ‘the first double-sided village well was dug up in 1800 A.D. using 419811 bricks!’ The background on the social divides and the various land legislations denying the basic rights to land ownership to the untouchables in the community have been elaborated. The author’s comments on the unjust social system have been elaborated. The author observes that there is no comparable example in the world of an unjust, discriminatory and unequal social system prevalent in India but also refers to the emergency of leaders with enlightened vision – he quotes Karl Marx, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar and Jawaharlal Nehru in the same paragraph. He also refers to the stellar role of the local Dalit hero, Babu Mangu Ram Mugowalia, as a revolutionary for the cause of social justice. He concludes the first chapter on a hopeful note – ‘social change demands dedication and courage from all the segments of society; there is a dire need of rational outlook in life; the Dalits are keen that the entire country becomes prosperous.’

The chapter titled, ‘A Thick Writing on a Blank Paper’ gives a graphic account of the situation of the Dalit community living on the periphery of the village called ‘Chamarali’ vis-à-vis the interaction with the upper caste ‘Jatt’ community. The scene of the distribution of ‘Prashad’ in the Gurudwara made a mockery of all the subtle teachings and the tall claims of the practice of equality among the Sikhs in a Punjab village. The author has exactly reproduced the piercing degrading remarks laced with un-uttered abuses hurled at the low caste children by the Sikh priest. We are also introduced to interesting characters like Gurdas claiming ‘possession’ by the Peer (dead Muslim Saint) and a few members of the author’s family including his father, Thakar Das. There is the most memorable and touching incident when the author, as a small child, is hung up side down in the well by his father to frighten and forbid him against eating the soil. It was the intervention of his mother which saved the day for the author. There are references to the utterly unclean food and drinks in the home including the white worms infested gur i.e., jaggery used to make tea. The lack of proper protective clothes in the winter season for the children of the Dalit community has also been described with wit and pathos. The description of attack of the locusts in the village and the experience of the author (he was then studying in the second grade in the school) of eating the fried locusts are indeed touching! The next chapter, ‘The Story of the Cracked Mirror’ presents the reader with a rare account of the verbal clash between a high caste Jatt and Phuman, a tenth class student of the Dalit community and a cousin of Madhopuri. The shortage of household requirements including the food grains in the Dalit homes have been vividly described explaining the resultant miseries. The author’s childhood nickname, ‘Good’ ie ‘ a male doll’ also tells the readers his humiliating experiences of ‘Bhitt’ ie untouchability, an ‘untranslatable’ word indeed, and also refers to the severe skin disease common among children of the untouchables.

The chapter entitled ‘The Flowers of the Wild’ presents an interesting picture of the female characters in the author’s family including the strong minded and colourful, Grand-Mother. During discussions in the family, the stories of Brahamanical mythologies including those of strange-bodied gods are ridiculed. The glorification and sanctity of the vegetarianism are also challenged, quoting counter historical and other sources. The tensions in the village, particularly during the difficult period of heavy rains, are described by the author in a very interesting manner. The author also touches upon the acute financial difficulties faced by his family and the unfulfilled hope that his maternal uncle who is a high official would be able to help the family in getting a regular job for the author’s father or his elder brother. The author returns to give to the reader a more intimate portrayal of his grand-mother, particularly her fondness in earlier times for the cattle meat. The pent up feelings of the author’s father find bitter expressions: “They worship the cattle…we are considered worse than animals…they say, keep off, you will make us unclean!” The chapters titled, respectively, ‘Travellers of Thorny Paths’; ‘Sun Gazing through the Clouds’; ‘Our House, Home of Sorrows’; ‘Brahama’s Empty Vicious Circles’; ‘Hunger and Thirst have no Caste,’ The tangle of Kinship’; ‘The Drought in Rainy Season’ bring out most realistically the pains and sufferings of the author’s family viewed both from the angles of an innocent child and a literary artist. The image of the IAS maternal uncle looms large at several places – as a role model and also for his inability in bailing out the family.

The chapter ‘The Banyan Tree’ provides a live portrayal of the most popular place for the community life of the Dalits of the village. The shelter of this big-ancient tree was even used to carry out the various small time professions including plying the handlooms. The author was studying in the 10th class when this banyan tree was cut down by the order of the village panchayat and it was indeed the end of an era and a whole world came down crumbling with the tree. Symbolically, the grandmother of the author did not survive this tragedy. The chapter titled, ‘A River Flowing in the Desert’ describes at length an extremely good natured family of the Jatt caste of Baba Arjan Singh which remained the best of friends of the author’s family till their last – “now when I recall the genuine affection of this Jatt family soaked in all the pores of my body, I feel that he (Arjan Singh) was a river in the desert of the life of our family; it did result in sprouting of some greenery”.

The chapter of the book titled, ‘Hatred with My Name’ recounts several bitter experiences of the author during the period of his early youth. He is frank and bold in stating that he felt ashamed over the large size of his family. He could even dare to tell his mother that he did not need any more brother or sister and that he felt terribly shy while carrying the younger sisters around. When the mother somehow mentions the author’s remarks to his father, his ringing comment needs to be quoted in original, “Saala Angrezan da, laapia mattan den…tere kahe main raddi hoke ghar bah jaaman”, translated loosely, ‘you, brother-in-law of the English, you dare advise me…do you think I should become a ‘wasted’ good for nothing fellow, sitting at home on your suggestion’. The author mentions that he wanted to tell that the small house was so overcrowded with ten persons including several animals under the same roof during the winter. The author refers to the environment in the college in 1972 when the students had resorted to a 39 days’ strike. During the studies in the college, he became deeply interested in the progressive literature and came closer to the Community Party of India in 1974-75. The poems written by him expressing anti-American sentiments were regularly published in the CPI Daily Nawan Zamana and other magazines and he felt convinced that India also needed a revolution like the Soviet Union, ‘ with economic equality established with some magic and where there were no caste distinctions in the society’. He also joined the college for doing post-graduation in Punjabi in Jalandhar and came into contact with sympathetic teachers and also became friendly with the militant poets like Pash and Sant Ram Udasi.

The author got a job in the Food Corporation of India in 1978 and continued his involvement with the activities of the Union. He was, however, to discover soon the narrow mindedness and weaknesses of character of many so-called progressive colleagues. The next turning point in the life of the author was his selection for a Class-II non-Gazetted Officer in the Press Information Bureau in 1983. The rise of the extremists Khalistani movement in the Punjab deeply upset him. The chapter titled, ‘Literature and Politics’ contains telling comments describing the situation during this dark period. The family of the author was immensely relieved when he was transferred to Delhi in 1987. The next two chapters describe respectively the author’s accidental encounter with the terrorists and also a hypocritical Guru in Delhi. The last chapter of the book, ‘The Curse of being a Tenant’ describes all the attendant difficulties of renting an accommodation in Delhi – with the caste factor also playing a role for the author.

The two hundred page book by Madhopuri is certainly a landmark in the category of autobiographical writing in Punjabi literature. The eminent novelist Gurdial Singh has earlier written powerful and sensitive prose describing the trials and tribulations of the marginalized people in rural Punjab. Madhopuri has, however, brought alive the physical pains and the deep sufferings of the souls of those at the bottom of the caste divides – an area which has hitherto remained almost untouched in Punjabi literature. It is hoped that Madhopuri’s autobiography would soon be available to a wider spectrum of readers in translations in Hindi (already published by Vani Prakashan, Delhi) and English. To capture the exact nuance of lyrical prose in the typical dialect of the Punjabi of the Doaba would indeed be a challenge for the translators. A Dwarfed Tree – an autobiographical diagnostic of Dalithood - certainly needs to be studied for the bigger issues and larger perspectives of the social and economic scene in India in the beginning of the 21st century.

(The reviewer has recently retired from the Indian Foreign Service.

e-mail : baal.anand@gmail.com)

1 comment:

Excellent Review and remarkable life story. I wish, those of your colleagues in such civil services get some insights like yourself in writing or doing services to Dalits in every or any ways they can. If all the educated mass of dalits were conscious enough about this society, dalit society would have reached to a greater heights, just because the educated Indians and educated dalits betryaed the poor and needy citizens of India, this nation is an aparthied and poverty riddent nature with deadly discrimination against each other, while they trumphet everywhere that India is shining and India incredeble??? while 700 million Indians make a pitiable less than dollar income, what a nation that our people made India into?.

Thanks for such a wonderful and touching review.

Dr.Saint,

http://upliftthem.blogspot.com

http://greatscholar.blogspot.com

http://jaibhimmedia.blogspot.com

Post a Comment